Marginalia

Home

About Marginalia

Current Issue

Archived Issues

Notes to Contributors

Links to Other Online Journals

Marginalia -- The Website of the MRG

(Proverbs 14:3)

In the Estoire de Merlin1 , Viviane and Merlin's love affair is illustrated and narrated intermittently through the use of manuscript illumination and the technique of interlace, with formulas indicating a change in the characters and/or in the spatiotemporal situation, allowing the narrative to switch from one episode to another and to return to previous sections.2 The text originates in 13th-century Old French manuscripts and was translated into the Middle English Prose Merlin in the 15th century. The story of Robert de Boron and, more precisely, the Suite Vulgate section, or Vulgate Sequel3, which treats events leading to the final imprisonment or "enserrement" of Merlin, is punctuated by these rendez-vous. They are patterned along similar lines and contrast with the more usual succession of battle scenes and political episodes in the romance.

What kind of narrative style is chosen for the development of this love affair and what does the use of manuscript illumination tell us about its importance within this romance? The discontinuity or uneven pacing which characterises the narration of Merlin and Viviane's relationship is apparent through the series of meetings they have, but the narrative techniques give coherence to the love plot and lend drama to its conclusion.

The romance is densely structured by the interlace pattern which allows the narrative both to sprawl and to maintain a formal structure, but iconographic insertions are rarer and vary according to the manuscripts. The (very literal) Middle English 15th-century translation of the Old French text survives in only one manuscript exemplar (Cambridge, U.L. Ff.3.11.4) , which does not have miniatures, whereas the Old French versions and manuscripts of the Merlin include iconographic representations of Merlin and Viviane's love story. This is not very surprising when we take into account the development of the French-inspired Arthurian romance tradition in English. If the Prose Merlin does not have the miniatures which parallel and emphasise the structure of the text in the illuminated French manuscripts, it does retain the interlace pattern which is so fundamental to the writing of the romance and which has also been used to distribute the illustrations. In the illuminated manuscripts, the selection and representation of different love episodes demonstrate different readings of this plot and show how marginal it remains within the romance genre, despite its importance in the narrative construction and its effects on the relationship between Merlin and the Lancelot Grail cycle.

1. Fragmentation and interlacing: the adventures of Merlin and Viviane as narrative counterpoints

1.1 Merlin's destiny

Fate seems to dictate the outcome of Merlin and Viviane's love story as Diane's pagan prediction to Viviane's father, Dyonas, shapes the progress of the narrative.

| "Dyonas, je t'en crois bien, et li dix de la Lune et des Etoiles si face que li premiers enf�s que tu auras femele soit tant couvoitie del plus sage home terrien apr�s ma mort [�] qu'il li ensaint la greignor partie de son sens par force d'yngremance, en tel maniere qu'il soit si sougis a lui, d�s qu'il l'aura ve�e, qu'il n'ait sor li pooir de faire riens encontre sa volent�. Et toutes les choses qu'elle li enquerra qu'il li ensaint" (1055-56)5 | "Dionas," quod diane, "I graunte the, and so doth the god of the see and of the sterres shull ordeyne, that the firste childe that thow shalt haue female shall be so moche coveyted of the wisest man that euer was erthly or shall be after my deth, [�] that he shall hir teche the moste parte of his witte and connynge by force of nygremauncye in soche manere, that he shall be so desirouse after the tyme that he hath hir seyn that he shall haue no power to do no-thinge a-gein hir volunte, and alle thinges that she enquereth he shall hir teche" (307)6 |

Before his first meeting with Viviane, Merlin is aware of what lies in store for him and announces it allegorically to Blaise.7

Viviane seduces Merlin by her appearance, but she is also very wise, and her dialogues with Merlin can be read both as masterpieces of courtly rhetoric and as a kind of trade discussion or power struggle which leads the lovers to agree on a "contract". They are bound by their word, as Merlin acknowledges when he wishes Blaise farewell: "so haue I made hir couenaunt, and also I am so supprised with hir love, that I may me not with-drawen" (680). In fact, even though Merlin feels "deceived" (681) about his imprisonment by Viviane, the narrator points out that she "hym hilde wele couenaunt, ffor fewe hours ther were of the nyght ne of the day but she was with hym" (681).

When he first meets Viviane, Merlin's foreknowledge does not prevent him from succumbing to temptation:

| "Et quant Merlin i vint et il le vit si le remira molt an�ois qu'il li de�st mot. Et dist en son cuer et pensa que molt seroit fols se il s'endormoit en son pechi� que il em perdist son sens et son savoir pour le deduit a avoir d'une damoiselle et lui honnir et Dieu perdre. Et quant il ot ass�s pens� si le salua toutes voies" (1057) | "Whan Merlin hir saugh he be-hilde hir moche, and a-vised hir well er he spake eny worde, and thought that a moche fole were he, yef he slepte so in his synne to lese his witte and his connynge for to haue the deduyt of a mayden, and hym-self shamed, and god to lese and displese. And whan he hadde longe thought, he hir salued" (308-309) |

There is no logical relation between his thoughts and his action, and the syntax as well as the rhythm of this passage emphasise this paradox. Merlin's choice shapes his destiny as he risks his own damnation. The way in which Merlin falls in love in the Suite Vulgate is not merely the manifestation of his lust and of his devilish origin, but expresses an overpowering desire which gives his character a more 'human' quality.8

Merlin and Viviane's love story is structured according the principle of inversion. In encounter after encounter between the lovers, the reader witnesses the improvement of Viviane's mastery of magic. Each of these passages oscillates between singularity and repetition: these periodical reunions take place according to an iterative pattern from Merlin's arrival to his departure.

1.2 Love meetings in contrast with the rest of the narrative

A different relation to social regulations, common practices and expectations

Arthur's relationship with Guinevere, on the other hand, is less a love story than a strategic wedding planned by Merlin, but the magician finds himself involved in an affair which at first develops in parallel with his social and political functions and then separates him from them. His relationship with Viviane is also strikingly different from the relationship her parents have with one another: their marriage is mentioned just before Merlin's first encounter with Viviane. Patrimonial and territorial benefits, which had to be taken into account in medieval matrimonial negotiations between noble families, are not relevant to a relationship which takes place away from society and does not have any institutional, moral or even economic approval and recognition. Apart from their own verbal promises to each other, nothing formalises their unwitnessed alliance. Viviane's father, whose past and temper have just been sketched, disappears from the narrative after the presentation of her origins.9

Similarly, the function of Merlin's magic castle differs markedly from that of other, more conventional fortresses described in the narrative. It is not primarily an enclosed, secure place where knights and armies can seek refuge during battle or when they are travelling across the country. On the contrary, its orchard is its most important place and allows its inhabitants to enjoy the open air. When Merlin's enchantment disappears, only this orchard is preserved, according to Viviane's desire. The military and political functions and symbolism of the castle, which appear in the episode of the siege of Clarence, are not rendered important. Though Merlin assures Viviane: "I cowde here reyse a Castell, and I cowde make with-oute peple grete plente that it sholde assaile, and with-ynne also peple that it sholde defende", this statement is made only to emphasise the extent of his skill in magic. It is also immediately followed by the declaration: "I cowde go vpon this water and not wete my feet" (309) and other boasts which, in this context, take on a slightly burlesque dimension.

Enchantment and development of courtly wonders

The enchantment created by Merlin culminates with the courtly feasts that are held in the orchard of the castle.10 In the episode, everything is depicted as extraordinary or prodigious. Intensives and superlatives are used to describe the marvel which is stressed insistently: "thei merveilled gretly of the orcharde that thei saugh ther so feire ther noon was be-fore, and on that other side thei merveiled" as the courtly assembly "made the grettest ioye that euer was seyn in eny londe" and the spectators "saugh the feire orcharde and the daunces and the caroles so feire and so grete, that neuer hadde thei seyn soche in theire lives" (309-310). The depiction of this visual, phonic and sensorial enchantment seems beyond the narrator's descriptive abilities as he uses the topos of the inexpressible:

| "Si conmencierent les charoles et les danses si merveilloses que on n'en porroit la quarte partie dire de la joie qui illuec fut menee. Et Merlins i faisoit lever [�] un vergier ou il avoit toutes les bones odours del monde et flours et fruits si rendoient si grant douceur que ce seroit merveille a raconter. Et la pucele qui tout ce ot et voit est si esbahie de la merveille qu'el veoit" (1059-60) | "Thei be-gonne the caroles and the daunces so grete and so merveilouse, that oon myght not sey the fourthe parte of the ioye that ther was made. Merlin lete rere a vergier, where-ynne was all maner of fruyt and alle maner of flowres, that yaf so grete swetnesse of flavour, that merveile it were for to telle; and the maiden that all this hadde seyn was a-baisshed of the merveile that she saugh" (310) |

The marvel is clearly beyond any comparison, and its creation is a singular event happening in a courtly setting with no equivalent in the Arthurian world depicted in the Prose Merlin.

Love and courtliness

The encounters between the lovers and in particular the creation of the enchantments also refer to the entertainments of a refined society, "briogne ladyes and knyghtes and maydons and squyres" "so wele a-pareiled of robes and Iuewelles", which exceeds the example given by Arthur's court. Music, songs, and dances take place before little jousts and friendly fights but they are much more emphasised in Merlin's enchantment than at the engagement ceremony of Arthur and Guinevere.11

The love-talk which takes place between Merlin and Viviane is unique in the Estoire de Merlin and also greatly contrasts with Arthur's dreaminess and muteness when he falls in love with Guinevere and is absorbed in her contemplation (Walter 931-40). Viviane is conquered by Merlin's marvels, which demonstrate his magical prowess, and she declares that "ye haue don so moche that I am all yours". While she pressures him to share his knowledge with her, he demands her love in return:

| "Et d'autre part encore ne m'av�s vous donn� nule seurt� de vostre amour. �Sire, fait ele, quele se�rt� vol�s vous que je vous en face? Devis�s et je le vous ferai. �Je voel, fait il, que vous me fianci�s que vostre amour soit moie et vous avoeques pour faire quanqu'il me plaira quant je vaurai" (1062) | "I haue yet no suerte of youre love." "Sir," qoud she, "what suerte wolde ye aske? devise ye, and I shall it make." "I will," quod Merlin, "that ye me ensure that youre love shall be myn, and ye also for to do my plesier of what I will" (311) |

Their skilful banter is also punctuated by the love terms they use with each other: "feire frende", "feire swete frende", "ffeire maiden", "swete love".

An ambiguous representation of women

However, the overtones of these episodes sometimes conflict with one another, frequently switching from refined courtliness to open misogyny, which seems to relate the text to more satirical and popular forms of writings such as fabliaux.12 Viviane manages to get the upper hand and uses her charms to draw Merlin under her influence13, managing to learn his magic without sacrificing her virginity: "she tysed euer Merlin to come speke with hir, for he ne hadde no power to dele with hir a-gein her will, and ther-fore it is seide that woman hath an art more than the deuell" (419).

The Suite Vulgate, however, presents neither Viviane nor Merlin as the incarnation of evil. The situation is acknowledged to be complex and the narrative more or less implicitly justifies the behaviour of each character:

| "Nous ne trouvons pas lisant c'onques Merlins requesist vilenie a [Viviane] ne a autre femme. Mais elle le dotoit trop quant elle l'ot connePu el elle sot conment il fu engendr�s, et ensi se garnissoit elle contre lui" (1224) | "We fynde not in no writinge that euer he required eny vilonye of hir ne of noon other; but she it douted sore whan she knewe what he was, and ther-fore she garnysshed hire so a-gein hym" (418) |

The narrator uses the authority of previous texts in order to emphasise that Merlin's actions and attitude towards Viviane have consistently been interpreted as harmless and respectful. While the narrator's caution suggests potential concern regarding the magician's manners, any such suggestions are brushed aside: "the storie maketh no mencion that euer Merlin hadde flesshly to do with no woman, and yet loved he nothinge in this worlde so wele as woman, and that shewed well" (437). On the other hand, Viviane's diffidence is explained and is believed to justify the way she tries to master Merlin, though her desire for occult knowledge might also have seemed a bit dubious to readers.

1.3 Merlin's character: a key to interlacing episodes

Freedom to move...

The love affair is thus narrated in an intermittent way but the mention of Merlin's travels relates the love episodes to other passages also involving him: the interlace is not used in this context to introduce narratives surrounding other characters. The structure of the narrative is very clear thanks to different levels of subdivisions and the very repetitive interlace pattern used throughout. It provides a sense of unity and cohesion to episodes which often occur at wide intervals. Merlin "departs" from a place and goes to see Viviane. In the end of each episode, he leaves her and travels to another destination.14

This pattern makes it possible both to isolate the love episodes as distinct entities, and to show how they are inserted into but still remain marginal to the network of Merlin's activities. Merlin abandons the role of the counsellor to Arthur or to other characters in order to enjoy Viviane's company and to teach her magic before returning to his normal occupations. Each episode is self-sufficient and structured the same way despite variations in length and detail. Merlin's encounters with Viviane seem to fill the gaps between his other occupations, as the ambassador of kings in particular. Before the first encounter, for example (Wheatley 306-307), contrary to what he says to Leonce, Merlin does not immediately fulfil his duty as a messenger but meets Viviane for the first time in an encounter which he has already foreseen. His private life is thus distinct from his public role and exists on the margin of the political activities to which he is otherwise normally dedicated.

As a consequence, rendez-vous sometimes occur just before or after Merlin's meetings with Blaise. The fourth and fifth encounters of Merlin and Viviane, which are referred to very briefly in the narrative, take place just before his visits to Blaise, who writes down all that he has been doing. But in his last visit to his master, Merlin announces the fate he has seen in store for himself and says goodbye to Blaise just before meeting Viviane: "This is the laste tyme that I shall speke with yow eny more, ffor fro hens-forth I shall soiourne with my love, ne neuer shall I haue power hir for to leve ne to come ne go" (679); "Ne I may not come oute ne noon may entre, saf she that me here hath enclosed, that bereth me companye whan hir liked, and goth hens whan hir liste" (693).

The final inversion of each character's role is also manifested spatially, with Merlin's position being that of the itinerant agent coming to see Viviane, who remains the static point. Whereas he had previously come to her only when he was available, his final immobilisation contrasts greatly with her own ability to go in and out and to visit him as she wishes: "Ne neuer after com Merlin oute of that fortresse that she hadde hym in sette; but she wente in and oute whan she wolde" (681). It is thus interesting to see how the conclusion of the final meeting differs from the previous encounters. The immobilisation of Merlin does not correspond precisely with the end of the narrative, but whereas the previous love episodes were almost totally isolated and self contained, the "enserrement" of Merlin has important consequences in the Arthurian world from which he has been extracted and, in a way, confiscated by Viviane. By imprisoning him, she severs all his other contacts and keeps him for herself.

The enchanted enchanter

As the encounters with Viviane take place among Merlin's travels, on two occasions, they follow an episode where he manifests his talent as a prophet. Before their second meeting, he is able to describe as well as to interpret the dreams of King Ban and his wife (though his explanations are cryptic enough for the unfolding events to retain some mystery). If Merlin's prophecies apply to the events taking place in the Mort Artu, it is difficult to pinpoint the episodes to which they refer. The story of king Flualis's dream also occurs relatively close to Merlin's imprisonment. It is striking to see how different a role he plays in each case. Ironically, this expert in divination falls consciously into Viviane's nets. His predictions and complex interpretations give him a position of authority and prestige when he is among kings, but in his private life, he gives up his knowledge to Viviane and rapidly falls from his position of master to become mastered by his pupil. In the end, Merlin is the victim of what he has himself taught Viviane, and he becomes the witness of the wonders she is able to produce. His pupil's work is a testimony to her mastery of magic: "he loked a-boute hym, and hym semed he was in the feirest tour of the worlde, and the moste stronge, and fonde hym leide in the feirest place that euer he lay be-forn" (681). The relationship between Merlin and Viviane thus builds up to the imprisonment of Merlin and progressively sets up the conditions of his final disappearance. The magician cannot escape his fate but consents to abandon his power and his freedom for the sake of love. The dramatic trajectory of this character shapes the evolution of the love affair and determines the progression of the narrative.

Merlin's and Viviane's new relations to space and freedom highlight the inversion of their situation: Viviane has appropriated Merlin's knowledge and has become his superior. Merlin's formerly occasional retreats with his lover become his sole focus in life, his exclusive mode of existence, and the Arthurian history then goes on without him. Viviane puts an end to the prophet's involvement in the Arthurian world. The result of the quest for Merlin allows the Arthurian court to acknowledge and accept a disappearance which is necessary in the narrative before the Lancelot, where Viviane replaces him. The magician is finally deprived of his previous narrative functions by the ultimate consequences of his abandonment to her. The love plot is thus developed within a network of episodes whose subject and tonality contrast with the rest of the narrative. It is set apart from it but related to the core passages of the romance through the character of Merlin.

2. Illustration and marginality: the scarce representation of Merlin and Viviane's love story

The Middle English Prose Merlin is not illuminated, though the tradition of illuminating the Old French texts of the Merlin is rather important and continues from the 13th to the 15th century. But visual representations of the love plot seem only to occur in French manuscripts from the 13th and 14th centuries rather than from the 15th century, when the illuminations generally seem to be less numerous. Viviane is quite rarely represented in the manuscripts of the Suite Vulgate15, but if she does not appear in the most decorated at the Biblioth�que Nationale de France (fr. 95)16, she is still present in four of the eleven manuscripts of the B. N. F. which have more than two illustrations for the Merlin and Suite Vulgate17: B. N. fr. 110, 749, 770 and 912318, and also British Library Add. 10292. These manuscripts are geographically from the area of Paris, the North of France and Flanders19. In addition, B. N. fr. 9123, a Parisian manuscript dating from the beginning of the 14th century, has a twin manuscript, B. N. fr. 105, from which images of Viviane are absent, but which represents Merlin talking to Gawain in his prison of air. B. N. fr. 105 and 9123 are closely related manuscripts, and the master of Fauvel has worked in both of them20, but Viviane does not appear in the first and they also have very different illumination programs. Their illuminations differ in size (fr. 105 is always two columns wide and taller), in subject and in quantity (there are more miniatures in fr. 912321). Each of these manuscripts contains an illumination relating to the love story between Merlin and Viviane but apparently there is no typical way of illustrating their story. Each illuminator seems to create his own uniquely styled illustration of the love story, and among the collection of manuscripts there is neither a single prominent iconographic tradition nor any favourite placement used from text to text for the illustration. The pictures of Merlin and Viviane within the Old French illuminated manuscripts remain rather marginal and when they occur, they often appear only in a single image.

The iconographic network is selective but the isolation of the representations of Merlin and Viviane is interesting because it contrasts so strongly with the text's narrative technique, which consists of a series of meetings. It probably points to the marginality of their adventures in the romance. There is no iconographic tradition precisely related to this story: the illuminations are rare and vary according each manuscript. The lovers' meetings are recurrent, but they have only a partial illustrative treatment. If the scarcity of the miniatures does not stress the marginal aspect of this love story in the romance, perhaps the unconventional role played by Viviane22 and the ambiguous nature of her relationship with Merlin explain the kind of censorship which applies to the illustration of their adventures.

2.1 Staging and illuminating the first meeting: interruption or synthesis of the narration?

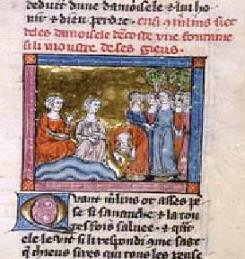

In general, the miniature related to their relationship is situated at the beginning of a passage relating one of their meetings, at the turning point marked by the use of formulas and interlacing. But in B. L. Add. 10292 f. 138c23, the illumination follows immediately the explanation of Viviane's origins and precedes the first encounter between Merlin and Viviane. So it does not correspond to the separation of two distinct episodes, even if it stresses the important moment when Merlin, after some hesitation, decides to go and talk to the maiden. The strangeness and the interruption generated by the miniature might be interpreted as an imitation of the oddity of this love story happening at all within the tale.

This particular illumination also causes the reader to look ahead to the extreme right of the double page and incites curiosity concerning a scene which the rubric and the story explain later on. The image interrupts the flow of the linear reading by pointing ahead to events that have not yet been narrated. Consequently, the reader already knows the conclusion of Merlin's internal debate because of the image and the rubric in the first meeting scene of B. L. 10292: "Ensi com merlins siet deles damoisele dencoste une fontaine si li monstre des ses gieus" (How Merlin sits near a maiden close to a fountain and how he shows her his games). It allows the reader to identify the characters and the scene and it distinguishes the enchanter and the magic he produces in front of Viviane his audience. But the miniature is ambiguous because for the reader, Merlin, staring at his own creation, is also presented in the miniature as part of the spectacle. In this enchanted world, Merlin and Viviane sit side by side, but Merlin is producing the enchantment and trying to impress his companion.

The miniature is organised in two parts with Merlin and Viviane on the right-hand side near a spring and a group of dancers on the left, with a forest in the background, and a "Iogelour" in the middle. The most striking element in this illumination is the central acrobatics rather than the relationship between Merlin and Viviane, which seems only a secondary element of interest for the illustrator, and remains marginal in the narrative. Representing an enchantment is a challenge for the writer and the illuminator, but this juggler is like a device highlighting the extraordinary nature of the scene. The illuminator does not only focus on the lovers near the fountain but seems specifically interested in the entertaining marvels created by Merlin. The "gieus" are translated as "pleyes" in the Middle English text, in which they refer to Merlin's games and really attract Viviane who keeps mentioning them and is eager to learn them. In the middle of the miniature, the body of one of the jugglers bent forward also seems to suggest the inversion which is going to take place when Viviane replaces Merlin as master of magic. His contorted body occupies the centre of the image and captures the attention because of its abnormal position. It thus contrasts with the restrained position of the lovers, which seems to reflect the fact that Viviane does not want to give herself to Merlin but prefers to observe his enchantments and to acquire his science and power. The games repeatedly mentioned in the text never evolve into love games. There is perhaps a humorous allusion to Viviane's cunning in this lexical insistence on "gieux", with its double meaning (game and sexual intercourse), as she manipulates Merlin and takes advantage of him. The irony is that she is interested in magic games exclusively whereas Merlin would prefer love games.

| "Vous me sambl�s a estre si douce et si debonaire que pour la vostre amour vous mousterrai une partie de mes gix par couvent que vostre amour soit moie, que autre chose plus ne vous demant" (1059) | "ye seme to me so plesaunt and deboneir, that for youre love I shall shewe yow a party of my pleyes, by couenaunt that youre love shall be myn, for other thinge will I not aske" (309) |

When Merlin is about to leave, after having produced a series of enchantments, Viviane stresses that rather than admiring Merlin's illusions she wants to learn how to create them herself: "'How', qoud the maiden, 'feire frende, shull ye not teche me firste some of youre pleyes?'" (311). Viviane is not satisfied with being an observer, but wants to master and perform these enchantments and carefully writes down all that he teaches her:

| "Il li aprist a faire venir une grant riviere [�] et d'autres gix ass�s dont elle escrit les mots em parchemin tel com il li devisa, et elle en savoit molt bien venir a chief" (1061-62) | "He taught hir to do come a grete river [�] and of other games I-nowe, where-of she wrote the wordes in perchemyn soche as he hir devised, and she it cowde full well bringe it to ende" (312) |

Only the orchard remains, so the sudden disappearance of the enchantment created by Merlin, is suggestive of a very fleeting and fragile type of existence, which in turn reflects the way the love meetings punctuate the narrative in the Merlin: "Assembled a-gein the maidenes and the ladyes, and wente daunsinge and bourdinge toward the foreste fro whens thei were come firste; and whan thei were nygh thei entred in so sodaynly, that oon ne wiste where thei were be-com" (311).

The disappearance of the dancers is quite similar to Merlin's own departure at the end of his meetings with Viviane, and works as a kind of "mise en abyme" of his own personal story, as well as of the artistic process, which escapes its creator. In the end, Merlin's imprisonment may be the only way for Viviane to keep her enchantment going eternally. Whereas Merlin's first magic tricks are spectacular, Viviane is presented in the text as the creator of a single unique spell whose strength exceeds Merlin's own deeds. The imprisonment is also irreversible, and its permanence contrasts with the quick disappearance of most of the marvels conjured by Merlin.

2.2 Representation of the lovers' couple

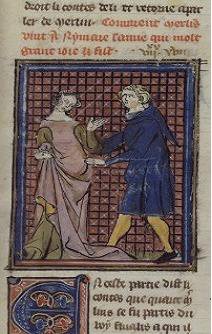

The illumination of B. N. fr. 9123 f. 28524 depicts Merlin and Viviane after king Flualis's dream and just before their fourth encounter, and corresponds to the situation of the interlace in the narrative. The two lovers are very simply depicted. Merlin moves towards Viviane and stretches his hand towards her. The expressions used in the narrative to describe Viviane's joyful welcome are much formalised25, and in the image, Viviane's attitude is also conventional in the sense that the illumination presents her in the position of a young bride before her husband, slightly bending the head as a sign of her submission26. The image in B. N. fr. 9123 seems to present an ordinary couple but the relationship between the lovers is more complex than the illumination suggests. Merlin and Viviane are far from being a married couple and the use of a traditional way of representing them conceals the singularity of a love story in which a woman manipulates her lover and finds ways of resisting his approaches. As opposed to the illumination of B. L. Add. 10292, this miniature does not stress the uniqueness of Merlin and Viviane's relationship, but perhaps corresponds instead to the narrative evolution of a love story which rapidly adopts a very repetitive pattern.

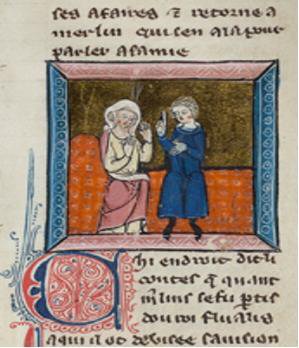

The miniature of B. N. fr. 770 f. 29127 is set indoors: the bed on which Viviane and Merlin are sitting, functions as a transition from the previous episode in the narrative, the dream of king Flualis, but mainly refers to the way Viviane protects her virginity from Merlin:

| "Et mengierent et burent ensamble et jurent ensamble en un lit. Mais tant savoit elle de ses affaires, quant elle savoit qu'il avoit volent� de jesir o li elle avoit enchant� et conjur� un oreillier que elle li metoit entre ses bras. Et lors s'endormoit Merlins" (1560) | "[They] ete and dranke, and lay in oon bedde; but so moche cowde she of his connynge that whan he hadde will to ly with hire she hadde enchaunted and coniured a pelow that she kepte in hir armes, and than fill Merlin a-slepe" (634) |

The image focuses on the discussion between the two lovers and Merlin's raised finger shows him in a position of authority, though this status is going to be challenged by Viviane's skills and her appropriation of the wizard's knowledge. The fact that the encounter takes place in a bedroom prepares the reader for the distortion of the normal educative scheme into the neutralisation and eventual overtaking of the master by his former pupil. But the pillow which plays an important role later in the narrative is not particularly highlighted in the image.

2.3 Merlin's disappearance

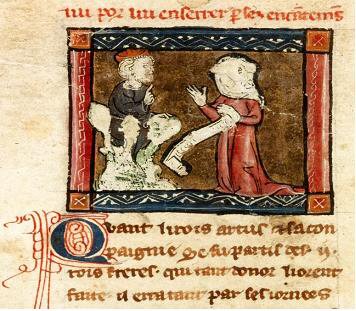

Viviane's "clergie" and the reversal of the learning relationship established with Merlin are interestingly depicted in B. N. fr. 110 f. 159v28. Merlin wears a hat which denotes his status as a teacher, and he looks as if he is in a pulpit, spatially higher than his student, but in fact he is in a prison made of trees or bushes. This symbolically recalls the wilderness of the forest of Broc�liande where his meetings with Viviane take place, but in this representation, Nature is more than a mere backdrop, as it obeys Viviane's will. The illuminator cannot or does not try to represent the prison of air but is inspired by other elements present in the text.

The rubric is interesting in the sense that it mentions two particular moments within the narrative: Merlin falling asleep and Vivian taking advantage of this to exercise her spell: "Ensi que merlins se dort desous i buisson d'aubespine et niniane sa mie fait son cerne tout entor lui por lui enserrer par sez encantemens" (How Merlin sleeps under a hawthorn bush and Niniane his friend makes a circle around him to entrap him through her enchantments). The miniature slightly differsdiffers slightly from this statement because Merlin is certainly not asleep under the bush but is instead emerging from it and conversing with Viviane. There is consequently a slight shift between the moment illustrated in the miniature and the legend, which gives a more comprehensive insight into the story. The position of Merlin's hand recalls his past authority, but Viviane's accessory, the scroll of parchment, refers to the greater knowledge that she has acquired under Merlin's direction. It symbolises the reversal of their respective positions. The scroll is traditionally the accessory of the lyric poet29, but here it literally contains the "carmen", the magic incantation used by Viviane. Through the scroll's performative effect, Viviane seems completely self-sufficient. She masters the action and the enunciation and possesses the ability to write, functions which had formerly been shared by Merlin and Blaise.

In this manuscript, where the illuminations are rather scarce (there are only sixteen in the Merlin portion30), the presence and choice of this miniature is very significant. It emphasises Viviane's relationship with Merlin and shows the circumstances of his disappearance. It is also the final miniature of the Merlin and thus iconographically closes the prophet's story, within a manuscript which contains the whole Vulgate cycle.

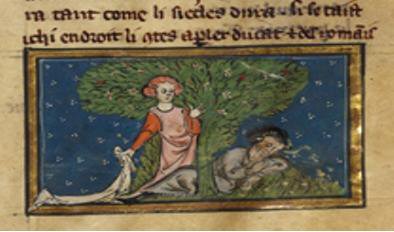

In the picture of B. N. fr. 749 f. 33131, where the same passage is illustrated, the "realism" of the picture and its correspondence with the text are rather more marked, as Merlin is indeed lying on the ground and sleeping under a blooming tree.

| "Il aloient main a main deduisant parmi la forest de Brocheliande, si trouverent un boisson bel et haut d'aubespines tous chargi�s de flours. Si s'asissent en l'onbre, et Merlins mist son chief en giron a la damoisele. Et elle li conmencha a tastonner tant qu'il s'endormi. Et quant la damoisele senti qu'il dormoit, si se leva tout belement et fist un cerne de sa guimpe tout entour le buisson et tout entour Merlins. Si conmencha ses enchantements tels conme Merlins li avoit pris" (1632) | "Thei wente thourgh the foreste hande in hande, devisinge and disportinge, and this was in the foreste of brochelonde, and fonde a bussh that was feire and high of white hawthorne full of floures, and ther thei satte in the shadowe; and Merlin leide his heed in the damesels lappe, and she be-gan to taste softly till he fill on slepe; and whan she felt that he was on slepe she a-roos softly, and made a cerne with hir wymple all a-boute the bussh and all a-boute Merlin, and be-gan hir enchauntementz soche as Merlin hadde hir taught" (681) |

A magical atmosphere is created by the dotted or spotted background (this kind of setting reappears in other miniatures) which here echoes the white flowers in the tree. The contrast between the two characters is reinforced by the fact that Viviane is standing, vertical like the tree, whereas Merlin is lying on the grass. No scroll is visible, but in this manuscript, Viviane makes circles around her lover with her "guimpe", a piece of her clothes. (It is interesting that, as it appears perhaps more in the Middle English text, the "scroll" interpretation coincides with the etymological meaning of the germanic word "Wimpel" which also refers to a streamer).

But if this image is more faithful to the text, its location within B. N. fr. 749 seems less directly relevant. Indeed, contrary to B. N. fr. 110, the miniature is not situated at the beginning of the "enserrement" episode, but alongside the previous passage, before Gawain's attack of the castle de la Marche. In B. N. fr. 749, the end of the "enserrement" episode is marked by another miniature which closes it but also questions the order of the story. The miniature of B. N. fr. 749 f. 333 shows Merlin and Arthur saying goodbye to each other, but this does not correspond with the next scene, when Arthur sends his knights to look for Merlin. It creates an analepse and a reorganisation of the story, as Merlin had prepared his farewell ("c'est la daerrainne fois" (1628)) and foreseen his future imprisonment before going willingly to meet his lover and his fate. Thus this illumination recalls a previous episode within the story and plays with the narrative chronology, but by doing so, it reflects the process of interlacing which allows the story to jump back from Merlin's departure to Arthur's court and to his mourning after the reminder of Merlin's foretold disappearance.

| "Ne onques puis Merlins s'en issi de cele forteresce ou s'amie l'avoit mis. Mais elle en issoit et entroit quant elle voloit. Mais ici endroit se taist li contes de Merlin et de s'amie. Et retorne a parler del roi Artu. Ensi com il fu mornes et pensis del departement de Merlin.

Or dist li contes que cele eure que Merlins se fu partis del roi Artu et qu'il li ot dit que c'estoit la daerraine departure [�]" (1632) |

"Ne neuer after com Merlin oute of that fortresse that she hadde hym in sette; but she wente in and oute whan she wolde. But now moste we reste a-while of Merlin and his love, and speke of the kynge Arthur.

The same hour that Merlin was departed fro the kynge Arthur, and that he hadde seide how it was the laste tyme that he sholde hym se [�]" (681) |

The miniature thus functions as an illustration of the mechanism of interlacing and of the very sentence which opens a new scene in the narrative, rather than as a representation of the actual order in which the story unfolds.

The closing of the illumination program of B. N. fr. 10532 shows Merlin in his air prison, talking to Gawain. Viviane is not directly present in the miniature, which nevertheless depicts the consequences of the love story. The miniature appears with the interlacing at the beginning of the episode where Gawain is transformed into a dwarf after his meeting with a couple in the forest.

Two marvels are thus presented in the picture: Gawain's temporary transformation33 and Merlin's final imprisonment before his total disappearance. Each of these spells has been cast by a woman. In Gawain's case it is transitory and has a very comical effect. But Merlin disappears and thus endures a kind of death in the Arthurian world. He has been the willing victim of an enchantment which renders him invisible before he finally becomes inaudible.

| "Moi ne verr�s vous jamais, ce poise moi, car plus n'en puis faire. Et quant vous departir�s de ci jamais ne parlerai a vous ne a autre, fors a m'amie. Car jamais nus n'aura pooir que il puisse ci assener pour riens que aviengne. Ne de chaiens ne puis je issir, ne jamais n'en isterai" (1652) | "Me shull ye neuer se, and that hevieth me sore that I may do noon other; and whan ye be departed fro hens, I shall neuer speke with yow no more, ne with noon other saf only with my leef; for neuer man shall haue power hider for to come for nothinge that may be-falle. Ne fro hens may I not come oute, ne neuer I shall come oute" (693) |

The marvel appears through the halo which surrounds him and represents his air prison. It is indeed a challenge to represent an invisible character, and the illuminator does not try to give an original illustration of the magic prison as it is described by the text:

| "el monde n'a si forte tour come ceste est ou je sui enserr�s. Et se n'i a ne fust ne fer ne pierre, ains est sans plus close del air par enchantement, si fort qu'il ne puet estre desfait jamais a nul jour del monde" (1652) | "in all the worlde is not so stronge a clos as is this where-as I am, and it is nother of Iren, ne stiell, ne tymbir, ne of ston, but it is of the aire with-oute eny othir thinge be enchauntement so stronge, that it may neuer be vn-don while the worlde endureth" (693) |

The prison can only be described in negative ways as it eludes categorisation. Merlin's existence is defined by the negative as he lists all the losses he makes, and the repetition of the adverb "never" shows how ineluctable is the fate from which he cannot escape. The negations reflect the restriction of Merlin's power and close his narrative horizon: Arthur "shall me se neuer more ne I hym, for thus is it be-falle. Ne neuer shall no man speke with me after you, ther-fore for nought meveth eny man me for to seche; ffor youre-self, a-noon as ye be turned fro hens, ye shull neuer here me speke" (693).

The use of the cloud in the illumination allows the illuminator to go beyond the characteristics of the prison and to focus on its marvellous aspect. A manifestation of the supernatural, clouds are often used in illuminations to represent God's appearances or his heavenly presence. The reader can see in the miniature more than can Gawain himself, who "loked vp and down, and nothinge he saugh, but as it hadde ben a smoke of myste in the eyre that myght not passe oute" (692-93).

Merlin says goodbye before his disappearance in the Lancelot, and the final miniature of B. N. fr. 105 pays homage to the magician whose story is coming to an end. The character of Merlin has outlived his usefulness within the narrative and is replaced by Viviane. For Paul Zumthor, his disappearance is a result of the instrumental aspect of the character34. He has lost his symbolic, poetical meaning. He is used in the romance as a character to be included in fight narratives, and for his prophetic or magical gifts, but he is not related to the stories surrounding such characters as Galahad or Lancelot. His adventure with Viviane thus allows him to be removed from the narrative before Lancelot's birth.

Merlin has made some predictions regarding the future of the Arthurian kingdom but he will not be present to prevent its downfall. The miniature stages the disappearance of Merlin and manifests a shift in the narrative focus, from the magician to the knight. The Arthurian battles and Merlin's negotiations will be replaced by knightly adventures. The illumination of the disappearance of Merlin, at the end of the narrative, is presented as the ultimate consequence of his relationship with Viviane, and thus emphasises its negative aspect. Merlin's loss is not redeemed in the illustrative program of B. N. fr. 105 by any reference to what he enjoys and receives later on from Viviane: once she has trapped him, she gives him her love.

In the various illuminated manuscripts we have considered, the miniatures which focus on a remarkable encounter (like B. L. Add. 10292, which is sensitive to the circumstances of their first meeting); present Merlin and Viviane as an archetypal couple (B. N. fr. 9123 and 770); show Merlin's "enserrement" by Viviane (B. N. fr. 110 and 749); or dismiss the love story to place emphasis on its final consequences (B. N. fr. 105) stress different aspects of the love affair. They usually provide a modified illustration of the episode into which they are inserted, though they are also sometimes vague (B. N. fr. 9123) and thus can conceal the complexity of the text. In B. N. fr. 110, the illumination schematises and synthesises the development of the narrative. The image consequently offers a reading of the text which, at first glance, can seem misleading. However, these gaps create suggestive interactions and opportunities for interpretation. The illuminations appear at a few important stages in a narrative where these adventures remain marginal. The textual inscription of the love plot in the romance is intermittent, and the illuminations, when there are any, accentuate the process of selection regarding episodes which, though limited and self-contained, are nevertheless of prime narrative importance.

2.4 The absence of illumination in the Prose Merlin

Whereas many of the Old French manuscripts of the Merlin and Suite Vulgate are illuminated, the only surviving exemplar of the Middle English Prose Merlin and Sequel is not. This would seem partly to be a consequence of the relatively low status of English compared with that of French, and also perhaps the result of a deliberate choice regarding whether or not the work deserved to be made into a luxury manuscript. For the most part, the illumination of secular and vernacular manuscripts is rarer than and inferior to that of religious books written in Latin. Within the hierarchy of vernacular languages, French also has a special status in England for obvious historical, social and political reasons. This Middle English text is thus distinct from the most refined 15th-century Old French versions of the Merlin produced for sovereigns and nobles, in France and beyond its borders. But the Old French prose text was still appealing enough in 15th-century England for the emergence of a Middle English translation. According to Carol Meale, this version of the text circulated both among aristocratic circles, as the Cambridge manuscript testifies35, and among a more middle-class audience, as is the case for the fragment preserved in Bodleian Rawlinson D. 91336. The absence of illumination in the Prose Merlin is not surprising when one considers the nature and characteristics of contemporary Middle English manuscript production.37

3. Conclusion

The episodes recounting the meetings between Merlin and Viviane follow the same narrative pattern and lead ineluctably to Merlin's imprisonment as a result both of his increasing love for Viviane and of the knowledge and skill she acquires from him. Merlin's fate is to be stripped of all the power he has acquired and to be forced to abandon his political functions as a counsellor of king Arthur. The passages dedicated to this "romance" have a singular and special status in the text, where their subject, their tonality and the issues they raise contrast with those of the work into which they are inserted. It opens a space for the development of the wonders created by Merlin and allows the relationship between him and Viviane to grow outside of any social control or recognition. The use of the interlace structure gives coherence to these marginal elements within the very dense material of the romance. It involves the rewriting and the combination of varied segments of texts presenting a wide variety of subjects and genres38. The illuminations occur at much wider intervals than the interlace device but they use the same frame. The image is thus part of the composition of the narrative and is the result of a process of selection and concentration which allows for different readings of the text. The rare manuscripts in which episodes from the love story are illuminated focus on different aspects of it: Merlin's gifts as a magician, a stereotypical love story, the imprisonment and fall of Merlin. The interlace pattern distributes the material and organises it, revealing the architecture of the whole. But the scarcity of images relating to marginal episodes such as the meetings between Viviane and Merlin show how secondary they are in the hierarchy of the narrative elements. Or perhaps these adventures represent Merlin in a way that creates a reluctance on the part of illustrators to exhibit them and a repression of this more disturbing part of the romance. A comparison with the Tristan and Iseult love story and its illumination39 is striking, and the difference appears in the very nature and focus of the two romances: in the Merlin, the love plot is secondary, whereas in the Tristan it lies at the heart of the narrative. Even in the most decorated manuscripts of the Merlin, this story is scarcely represented and thus does not lead to the development of a specific iconographic tradition. The need for selectivity, concentration and economy can explain the tendency to avoid visual repetitions, as the rendez-vous are textually developed in very similar and repetitive ways. Nevertheless, it does not apply to the battle scenes which are both heavily narrated and illustrated in the romance. The skill and originality of the artist must also be considered, as well as the means of the patron who might have ordered the book, his own interests and those of the individual overseeing the manuscript production.

Appendices:

1. The meetings between Merlin and Viviane

| Suite Vulgate (Walter) | Prose Merlin (Wheatley) | |

| I. | Et si tost come Merlins se fu partis de Leonce, si s'en ala pour veoir une pucele de molt grant biaut� [�] Mais an�ois li demanda la pucele quant il revenroit et il li dist: "La veille Saint Jehan". Ensi s'em parti li uns de l'autre (1055-63) | As soone as Merlin was departed fro Leonces he wente to se a maiden of grete bewte [�] er he departed the maiden hym asked whan he sholde come a-gein; and he seide on seint Iohnes even; and thus departed that oon fro that other (307-312). |

| II. | Ala a s'amie qui l'atendoit [�] Et lors s'em parti Merlins de li et s'en vint a Benuic (1223-25) | Merlin wente to his love [�] and than Merlin departed from hire and com to Benoyk (418-419) |

| III. | Lors s'en parti Merlins et vient a Viviane s'amie [�] Et puis s'en ala el roiaume de Lambale (1452) | Than departed Merlin, and com to Nimiane his love [�] and than he wente in to the reame of Lamball (565). |

| IV. | Prist congi� as .ii. rois et as .ii. ro�nes et as autres barons et s'en repaira a s'amie [�] puis s'em parti et s'en vint droit a Blayse son maistre (1525-26) | He toke leve of the two kynges and the Quenes, and of the other barouns, and repeired to Nimiane [�] and than departed and com to Blase, his maister (612). |

| V. | Onques ne fina devant qu'il vint el roiaume de Benuyc et s'en vint droit a Viviane s'amie [�] Si s'entrecomandent a Dieu molt doucement. Et lors s'en vint Merlins a Blayse son maistre (1559-60) | He com to the reame of Benoyk, and yede to Nimiane [�] eche of theym comaunded other to god full tendirly; and than com Merlin to Blase his maister (634-635) |

| VI. | Lors s'em parti Merlins de Blayse, et il erra em petit d'ore tant qu'il en vint a s'amie [�] Ne onques puis Merlins s'en issi de cele forteresce ou s'amie l'avoit mis. Mais elle en issoit et entroit quant elle voloit (1630-32) | Than departed Merlin from Blase, and in litill space com to his love [�] Ne neuer after com Merlin oute of that fortresse that she hadde hym in sette; but she wente in and oute whan she wolde (678-681) |

2. Table describing the reference manuscripts:

| Deposit | Classmark | Origin | Date40 | Merlin | Suite Vulgate | Version | Miniatures

M + SV |

| Paris, B. N. F. |

fr. 770 | Douai | 1285 | 122-149 | 149-312v | a | 118 |

| Paris, B. N. F. |

fr. 749 | Ghent Th�rouanne |

1280 | 123-165 | 165-338 | contaminated | 96 |

| Paris, B. N. F. | fr. 110 | Th�rouanne Cambrai |

1290 | 45v-67 | 67-163v | b | 16 |

| London, B. L. | Add. 10292 | Ghent Th�rouanne |

1316 | 1-76 | 101v-214v | b | 176 |

| Paris, B. N. F. | fr. 105 | Paris | 1315-35 | 126r-161v | 162r-349v | a | 77 |

| Paris, B. N. F. | fr. 9123 | Paris | 1315-35 | 96-131v | 131v-302r | a | 128 |

| Cambridge, U. L. | Ff3.11 | England | 1450 | 1-35v | 35v-245 | a | 0 |

3. The illumination of Merlin and Viviane's story in the Old French manuscripts

| Manuscript | Description of the miniature | Situation | Rubric | Page ref. (Walter) |

| B. N. fr. 770 | Merlin talking to Viviane | Chi endroit dit li contes que quant Merlins se fu partis dou roi Flualis� | 0 | 1559 (V) |

| B. N. fr. 749 | Merlin imprisoned by Viviane | En ceste partie dist li contes que quant li rois Artus et si baron orent desconfi les romains, et li rois ot ochis le cat, qu'il se mist au repairier. | 0 | 1625 (VI) |

| B. N. fr. 110 | Merlin imprisoned by Viviane | Quant li rois Artus et sa compaignie se fu partis des .ii. rois freres qui tant d'onor li avoient faite� | Ensi que Merlins se dort desous I buisson d'aubespine et Niniane sa mie fait son cerne tout entor lui por lui enserrer par sez encantemens. | 1627 (VI) |

| B. L. Add. 10292 | Merlin shows his games to Viviane | Quant Merlins ot asses pense si s'avanche et l'a toutes fois saluee� | Ensi com Merlins siet deles damoisele dencoste une fontaine si li monstre des ses gieus. | 1057 (I) |

| B. N. fr. 105 | Merlin imprisoned talks to Gawain | Ci endroit dit li contes que messire Gauvain chevaucha entour archie et demie puis qu'il se fu parti de la demoisele que li nains chevaliers conduisait. | Comment monseigneur Gawain fu muez en faiture de nayn et comment il parla � Merlin qui estoit enprisonnez. | 1649 |

| B. N. fr. 9123 | Merlin talking to Viviane | En ceste partie dist li contes que quant Merlins se fu partis du roy Flualis� | Comment Merlins vint � Nyniaie sa mie qui molt grant joie li fist. | 1559 (V) |

Miniatures

Image 141: B. L. Add. 10292 f. 138c

Image 2: B. N. fr. 9123 f. 285

Image 3: B. N. fr. 770 f. 291

Image 4: B. N. fr. 110 f. 159v

Image 5: B. N. fr. 749 f. 331

Image 6: B. N. fr. 105 f. 347

Ir�ne Fabry, U. of Cambridge

Previous |

Next |

1. Estoire de Merlin, The Vulgate version of the Arthurian romances, t. 2. Ed. H. Oskar Sommer, Washington D. C.: Carnegie Institute, 1908 [according to the manuscript British Library Add. 10292]; Le livre du Graal. I, Joseph d'Arimathie, Merlin, Les premiers faits du roi Arthur. Ed. Daniel Poirion and Philippe Walter. Paris: Gallimard, Biblioth�que de la Pl�iade, 476, 2001 [according to the manuscript Bonn B. U. 526].

2. For a study of the poetics of the interlace narrative technique, cf. Vinaver, Eug�ne. The Rise of Romance. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971, "The Poetry of Interlace", pp. 68-98.

3. It is called "Suite Vulgate" because it presents the most common sequel of the story of Merlin, as opposed to the "Suite Post Vulgate", also called Suite du Merlin, cf. La Suite du Roman de Merlin. Ed. Gilles Roussineau. Gen�ve: Droz, 1996, 2 vol.

4. Bodleian Library MS Rawlinson D. 913. contains a very small fragment of the Middle English Prose Merlin, found on a single leaf, folio 43.

5. Le livre du Graal. I, Joseph d'Arimathie, Merlin, Les premiers faits du roi Arthur. Ed. Daniel Poirion and Philippe Walter. Paris: Gallimard, Biblioth�que de la Pl�iade, 476, 2001.

6. Merlin, or the Early History of Arthur: A Prose Romance (About 1450-1460 A. D.). Ed. Henry B. Wheatley, London: K. Paul, Trench, Tr�bner and Co., EETS o. s. 10, 12, 36, 112, 1865-98.

7.

| "La leuve est el pa�s qui le lyon sauvage doit loiier de cerceles qui ne seront de fer ne de fust ne d'argent ne d'or ne d'estain ne de plomc ne de riens nule de terre qui aigue ne herbe port, si en sera estroit loii�s que mouvoir ne se porra. [�] Ceste prophesie chiet sor moi. Et si sai bien que je ne m'en saurai garder" (1050-51) | "in that londe is the wolf that the lupart shall bynde with cercles that shall nother be of iren ne steile ne tree ne golde ne siluer ne lede ne nothinge of the erthe ne of the water ne herbe, and shall be so streite bounde that he shall not meve. [�] �us moche I will telle yow, that this prophesie shall falle vpon me, and I wote well I may me not kepe ther-fro" (304) |

Later, once this prophecy has been fulfilled, Merlin admits in his discussion with Gawain: "I wiste wele that sholde be-falle" (694).

8. The song from the magic "carole", "Vraiement comencent amours en ioye, et fynissent en dolours" (310 � Truly, love begins with joy and ends in pain), applies very well to Merlin's experience. It determines the tonality of the passage and adds a touch of bitterness and of fatalistic resignation to a sequence which leads the narrative towards the final imprisonment of Merlin. On the unique preservation in the Middle English Merlin of a passage in the French language which is not translated, within meetings between Merlin and Viviane which are marked by linguistic alterity, cf. Fabry, Ir�ne. "Composition, illustration, translation: Ambigu�t� g�n�rique et esth�tique de la continuation dans la Suite-Vulgate du Merlin et le Prose Merlin", m�moire de Master 2, Universit� Lumi�res Lyon 2, 2005, pp. 68-70.

9. However, Viviane gives a dramatic insight into the necessity for secrecy in their relationship when she pleads Merlin to teach her his magic, which will make her father fall asleep and free her to meet her lover:

| "Pour ce, fait elle, que toutes les fois que je vauroie parler a vous que je endormiroie mon pere, qui a a non Dyonas, et ma mere, si que ja ne s'apercevroient de moi ne de vous. Car saci�s qu'il m'ocirroient si s'apercevoient de riens que nous fe�ssons" (1223-24) | "I wolde make my fader a-slepe alle the tymes that I wolde speke with yow, whos name is Dionas, and my moder, that thei aparceyve neuer of yow ne me, ffor witeth it well thei wolden me sle yef thei parceyved of vs two ought" (418) |

Despite his ambiguous relationship with the figure of Diane during his youth, Dyonas is eventually revealed to be a typical lord and servant of the king. As a father, he is an image of authority, of the norm and of social control and constraints, but he rapidly loses this role in the lovers' story.

10. The music and the dance held for this occasion have no equivalent in the romance (apart from the adventure of Guinebaut, which offers an interesting echo of this passage; 361-64). This kind of entertainment is described much more fleetingly on the occasions of the reception of King Ban and Bohort at Arthur's court (131-38) and the marriage of Arthur and Guinevere (447-48).

11. Similarly, the royal wedding leaves little room for courtly celebration: the False Guinevere episode (Walter 1287-1300) and the hostility of the younger knights and of those of the round table (Walter 1275-1287) spoil the merry atmosphere until the queen's intervention and Gawain's courtly pledge in a later tournament.

12. Micha, Alexandre. "La Suite-Vulgate du Merlin, �tude litt�raire", De la chanson de geste au roman, �tudes de litt�rature m�di�vale. Gen�ve: Droz, 1976, p. 451 ss.

13. According to Philippe Walter, in the 13th century Merlin's fate would have recalled the popular motif of the wise philosopher who, despite his caution regarding women, eventually becomes the consenting and ridiculous victim of feminine charms. Le livre du Graal. I, Joseph d'Arimathie, Merlin, Les premiers faits du roi Arthur. Ed. Daniel Poirion and Philippe Walter. Paris: Gallimard, 2001, p. 1821.

14. The table included below, which tracks the six meetings of Merlin and Viviane in the Prose Merlin, shows very clearly how the beginnings and conclusions of these passages are similarly shaped and written, particularly through the use of the formula "then departed Merlin". Cf. Appendices, 1) The meetings between Merlin and Viviane in the Prose Merlin.

15. Hoffman, Donald L. "Seeing the Seer: Images of Merlin in the Middle Ages and beyond", Word and Image in Arthurian Literature, pp. 105-150.

16. In some cyclical manuscripts of the Lancelot Graal (such as B. N. fr. 117-120), Viviane is not represented within the Merlin but at the beginning of the Lancelot. This choice is interesting as it reveals a focus on different aspects of the fairy's character.

17. These are B. N. fr. 91, 95, 96, 105, 110, 344, 749, 770, 9123, 19162 and 24394. For further details and descriptions, see the Catalogue des manuscrits fran�ais de la Biblioth�que nationale, D�partement des manuscrits. Ed. H. V. Michelant, Michel Deprez, Paul Meyer, C. Couderc, L. Auvray et alii. Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1868-1902, and to the Mandragore website http://mandragore.bnf.fr/ (01/05/2006).

18. Cf. Appendices, 2. Table describing the reference manuscripts.

19. Stones, Alison. The Illustrations of the French Prose Lancelot in Flanders, Belgium and Paris 1250-1340. Doctoral dissertation: University of London, 1970, ch. 6 and 9. References to the manuscripts of the Merlin are also found in Micha, Alexandre. "Les manuscrits du Merlin en prose de Robert de Boron", Romania, 79, 1958, pp. 78-94 and 145-174; Trachsler, Richard. "Pour une nouvelle �dition de la Suite-Vulgate du Merlin". Vox Romanica, 60, 2001, pp. 128-48. There are two versions of the Merlin and Suite Vulgate, a long one (a) and a short one (b) which appears most frequently in the manuscripts containing the whole Vulgate cycle.

20. Stones, Alison. "The Artistic Context of le Roman de Fauvel", Fauvel studies: allegory, chronicle, music, and image in Paris, Biblioth�que nationale de France, MS fran�ais 146. Ed. Margaret Bent and Andrew Wathey. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998, pp. 529-567.

21. Cf. Appendices, 2. Table describing the reference manuscripts.

22. For the different representation of Viviane in the Suite Vulgate and the Merlin Huth: Harf-Lancner, Laurence. Les F�es au Moyen �ge: Morgane et M�lusine: la naissance des f�es. Paris: H. Champion, 1984, pp. 291-315.

23. Cf. Appendices, Image 1.

24. Cf. Appendices, Image 2.

25. Stereotypical expressions reflect with subtle variations the joy his arrival always arouses:

Nimiane [�] was gladde and ioyfull as soone as she hym saugh (565)

Nimiane [�] made hym grete chire, and of hym was gladde and ioyfull (612)

She made hym the grettest ioye that she myght (634)

[She] grete ioye of hym made (680)

26. Garnier, Fran�ois. Le langage de l'image au Moyen Age. Signification et symbolique. Paris: Le l�opard d'or, 1982, vol. 1, p. 141.

27. Cf. Appendices, Image 3.

28. Cf. Appendices, Image 4.

29. On the distinctive representation of the author writing at his desk, an image which replaces that of the poet writing or reading aloud from his scroll in an outside setting, see Huot, Sylvia. From song to book: the poetics of writing in old French lyric and lyrical narrative poetry. Ithaca, London: Cornell University Press, 1987, pp. 246-47.

30. In the Merlin and Suite Vulgate, the ratio of illuminations to pages of text (1.3 illuminations for every 10 pages) is the lowest compared to all the other parts of the cycle; the most illustrated text is the Lancelot with 71 illuminations, but it has the same proportion of illustrations as the Mort Artu with its small total of five miniatures: 3 illustrations for every 10 pages of text.

31. Cf. Appendices, Image 5.

32. Cf. Appendices, Image 6.

33. The rubric indicates "Comment monseigneur gawain fu muez en faiture de nayn et comment il parla � merlin qui estoit enprisonnez": How messire Gawain was transformed into a dwarf and how he talked to Merlin who was imprisoned. It accompanies the narrative and announces what is going to happen. The rubric is also helpful for the interpretation of the image, in which Gawain's transformation is not immediately obvious and in which Merlin's air prison is difficult to represent.

34. Zumthor, Paul. "La d�livrance de Merlin", Zeitschrift f�r romanische Philologie, 62, 1942, p. 387.

35. The Cambridge manuscript is not a luxury copy with lavish illumination, though the quality is rather good: it contains no miniatures but three varieties of capitals: in decreasing size, painted initials with borders, blue and red golden painted initials, blue and red or violet and golden initials.

36. Meale, Carol. "The Manuscripts and Early Audience of the Middle English Prose Merlin", The Changing Face of Arthurian Romance. Ed. Alison Adams, Armel Diverres, et al., Woodbridge: Boydell, 1986, pp. 92-111.

37. For more on the audience and the manuscript transmission of the Merlin en prose and of the Prose Merlin, see Ir�ne Fabry, "Composition, illustration, translation: Ambigu�t� g�n�rique et esth�tique de la continuation dans la Suite-Vulgate du Merlin et le Prose Merlin", m�moire de Master 2, Universit� Lumi�res Lyon 2, 2005, Partie 2: Critique textuelle, perspective comparatiste et conditions de r�ception: les diff�rentes versions de l'Estoire de Merlin, pp. 60-93.

38. Combes, Annie Les voies de l'aventure: r��criture et composition romanesques dans le Lancelot en prose. Paris: Champion, 2001, p. 403.

39. Their story is very popular and has resulted in a lot of artistic representations with stereotypical elements (the lovers drinking the potion, the lovers' death, etc.) on a variety of materials (tapestries, ivory coffins, etc.). Roger Sherman Loomis, and Laura Hibbard Loomis. "The tryst under the tree", Arthurian legends in medieval art. London: Oxford University Press, 1938.

40. For the date and origin of these manuscripts, see Stones, Alison. "An approximate chronology and geographical distribution of Lancelot-Grail MSS with more than one illustration", Lancelot-Grail project, http://ltl22.exp.sis.pitt.edu/lancelot/Lant.asp (01/05/2006).

41. All the miniatures included in this article are reproduced with permission of the British Library and the Biblioth�que Nationale de France. I would like to thank Trinity College (Cambridge) for the grant from the Fellows' Research Fund which has allowed me to acquire these reproductions.